In the shadow of Mount Vesuvius, the bustling Roman town of Pompeii thrived as a hub of commerce, culture, and everyday joys until August 79 CE, when a cataclysmic eruption buried it under layers of ash and pumice. This disaster, long shrouded in mystery, preserved the city in a frozen moment of antiquity. Rediscovered in the 18th century through systematic excavations, Pompeii revealed not just ruins but a treasure trove of artworks, including some of the finest surviving examples of Roman painting. Among these stand the iconic frescoes and mosaics, vibrant murals that once adorned the walls of homes and villas. These pieces, mostly from the Roman period spanning the 1st century BCE to 79 CE, capture the essence of daily life, mythology, and social rituals in ways no other ancient site can match. Uncovered starting in the 18th century, they offer an unparalleled glimpse into Roman aesthetics, where elaborate Fourth Style frescoes from around 50 to 79 CE dominate with their fantastical architecture, bold colors, and theatrical flair. Sites like the House of the Vettii, Villa of the Mysteries, and House of the Faun draw crowds today, their walls still whispering stories of a lost world. As we explore these masterpieces, their technical brilliance reveals the sophistication of Roman artists, while their subjects illuminate beliefs, class structures, and the intimate rhythms of ancient society.

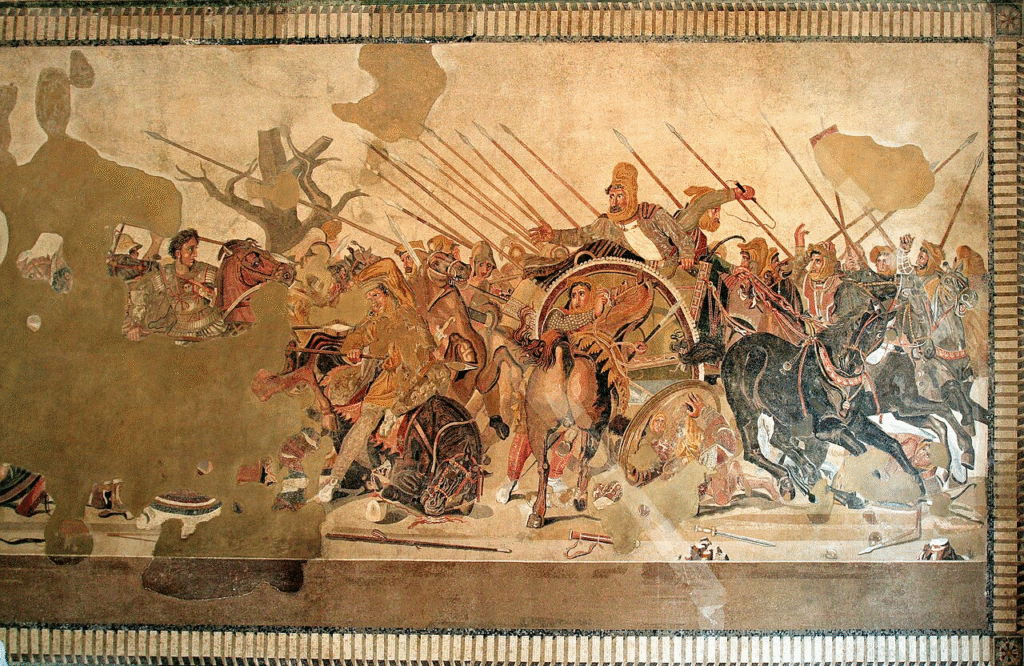

Alexander Mosaic (House of the Faun)

The Alexander Mosaic commands attention with its monumental scale and intricate detail, a floor masterpiece measuring over 5 by 3 meters that transforms a simple pavement into a battlefield epic. Crafted from tesserae of stone, glass, and shell in shades of red, blue, and gold, it depicts Alexander the Great charging against the Persian king Darius III at the Battle of Issus in 333 BCE, their faces locked in intense emotion as horses rear and soldiers clash amid swirling dust. This Hellenistic-inspired scene, copied from a lost Greek painting likely by Philoxenus of Eretria, showcases Roman admiration for Eastern conquests and heroic ideals, blending historical fact with dramatic storytelling to inspire awe in viewers. Found in the House of the Faun, a grand urban residence belonging to a wealthy elite family, the mosaic floored the exedra, a reception room where guests would recline and converse, its grandeur signaling the owner’s status and cultural sophistication.

What elevates this work to iconic status is its preservation and artistry; no other ancient mosaic rivals its emotional depth or technical precision, where shadows and highlights create a three-dimensional illusion on a flat surface. Though technically a mosaic rather than a fresco, it is inseparable from Pompeii’s wall paintings in discussions of Roman visual culture, often housed alongside them in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples (MANN) today. Unearthed in 1831, it underscores how Pompeian art bridged Greek traditions with Roman innovation, offering insights into the empire’s fascination with military glory and the divine right of rulers. For art enthusiasts, this piece is a cornerstone, reproduced endlessly in textbooks and museums, reminding us of Pompeii’s role as a cultural crossroads.

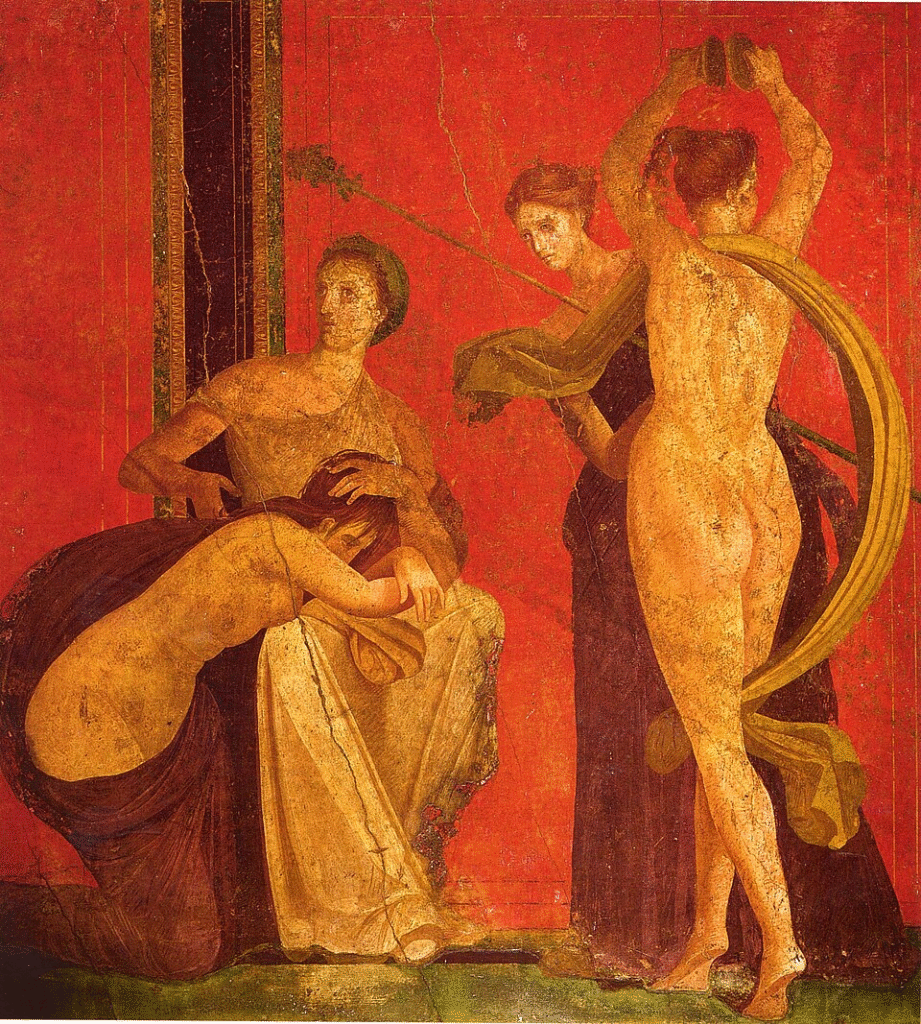

Villa of the Mysteries Frieze (Villa of the Mysteries)

Sweeping across the crimson walls of a suburban villa’s triclinium, the Villa of the Mysteries Frieze unfolds like a cinematic ritual, a continuous band of over 2 meters high depicting women and winged figures in a Dionysiac initiation ceremony. Vivid reds, yellows, and blacks animate the scenes: a young woman veiled and trembling before a fierce Pan, another whipping her with a rod, and a divine procession led by Dionysus himself, all rendered in the Fourth Style’s bold, illusionistic architecture that frames the action like a stage set. This enigmatic cycle, dating to around 50 BCE, likely celebrated the mystery cult of Bacchus, where elite women underwent secretive rites promising spiritual ecstasy and rebirth, reflecting Roman syncretism of Greek mythology with local beliefs in fertility and the afterlife. Located outside Pompeii’s walls in the Villa of the Mysteries, a lavish retreat for banquets and private worship, the frieze enveloped diners in its sacred narrative, enhancing the room’s role as a space for communal mystery.

Its fame stems from the puzzle it poses: scholars debate whether it illustrates a real initiation or symbolic allegory, but its raw energy and preserved colors make it one of antiquity’s most captivating frescoes. Most of the original remains in situ, drawing thousands to the villa annually for its immersive power, though some fragments reside in Naples. As a hallmark of Fourth Style innovation, with its fantastical columns and vibrant palette evoking theater backdrops, the frieze highlights Roman women’s roles in religion and the blend of terror and joy in cult practices. For cultural travelers, it transforms a visit to Pompeii into a journey through ancient spirituality, where art served not just decoration but profound transformation.

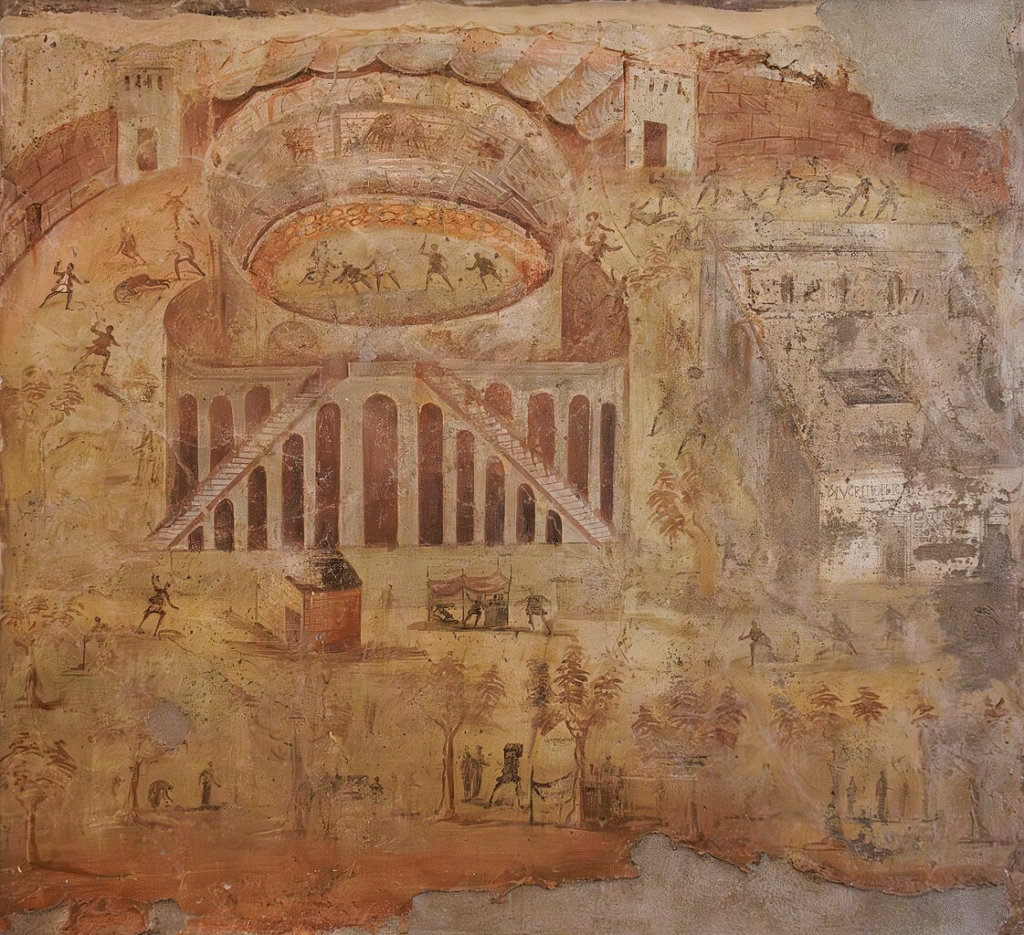

The Riot in the Amphitheatre (House of Actius Anicetus)

Chaos erupts in muted earth tones across a narrow wall panel, where gladiators clash with spectators in a frenzy of fists, clubs, and fallen bodies, capturing the brutal Riot in the Amphitheatre of 59 CE. This rare fresco, in the Fourth Style’s dramatic idiom, uses angular lines and crowded composition to convey disorder: Pompeians and Nucerians brawl amid the arena’s tiers, Roman soldiers intervening from above, all under a hazy sky that heightens the tension. Documenting a real historical event sparked by gladiatorial rivalries, as recorded by Roman historian Tacitus, it illustrates the volatile social fabric of provincial towns, where entertainment fueled class tensions and local pride. Housed in the House of Actius Anicetus, possibly owned by a gladiatorial sponsor, the painting likely adorned a tablinum or public-facing room, serving as a boastful or cautionary tale for visitors about civic unrest and imperial oversight.

Its significance lies in bridging art and history; unlike mythological fantasies, this scene offers a snapshot of Roman spectacle and conflict, making it a vital social document unearthed in the 19th century and now preserved in the MANN. Widely recognized for humanizing antiquity, it reveals the amphitheater’s role in community bonding and division, a precursor to modern sports rivalries. Art lovers appreciate its raw realism amid Pompeii’s more idealized works, underscoring how frescoes captured the gritty undercurrents of daily life.

The Baker Terentius Neo and His Wife (House of Terentius Neo)

Gazing directly at the viewer with poised elegance, this double portrait emerges from a black background in subtle ochres and whites, the faces rendered with lifelike precision that captures wrinkles, determined expressions, and subtle jewelry. The man, identified as Terentius Neo, a prosperous baker and possibly a magistrate, stands in a toga, while his wife, often linked in scholarship to the name Paquius Proculus in earlier interpretations but now firmly associated with the Terentius household, wears a stola with an elaborate hairstyle, embodying the Fourth Style’s shift toward intimate realism over grandeur, where portraits served as family heirlooms. This artwork, long debated in nomenclature but recognized as a single iconic piece from the House of Terentius Neo (also cross-referenced with Paquius Proculus elements in some records), highlights rising middle-class ambition in Pompeii’s stratified society, emphasizing literacy and marital partnership as markers of status in the late Republic. Displayed in a modest yet prosperous home on Via dell’Abbondanza, it probably graced the atrium, welcoming clients and asserting the couple’s respectability in public life.

This work’s iconic appeal comes from its accessibility; it humanizes ancient Romans, showing everyday people through portraiture that influenced later Renaissance artists. The original resides in Naples, but replicas evoke its presence in Pompeii’s excavations since the 19th century. It speaks volumes about gender dynamics and social mobility, making it essential for understanding how art reflected class structures and personal identity.

The Three Graces (House of Titus Dentatius Panthera)

Dancing in harmonious nudity against a deep red field, the Three Graces embody ethereal beauty with slender forms intertwined, their golden hair flowing and arms linked in a circle of unity, painted in the Fourth Style’s delicate, almost luminous strokes. Representing Aglaea, Euphrosyne, and Thalia, daughters of Zeus symbolizing splendor, mirth, and bloom, these figures drew from Greek mythology to invoke ideals of grace and Venusian charm in Roman homes. In the House of Titus Dentatius Panthera, a well-appointed residence, the fresco likely decorated a private cubiculum or garden-facing wall, fostering an atmosphere of refined pleasure and philosophical contemplation for the owners and their guests. Such mythological motifs underscored the elite’s cultural literacy and devotion to beauty as a divine virtue.

Renowned for its elegance and frequent reproduction in art history, this piece exemplifies Pompeian frescoes’ role in domestic harmony, its preservation rivaling Pompeii’s best. Viewed today in the MANN, it connects to broader Western traditions of classical iconography. For history enthusiasts, it reveals how Romans integrated myth into daily aesthetics, celebrating harmony amid life’s chaos.

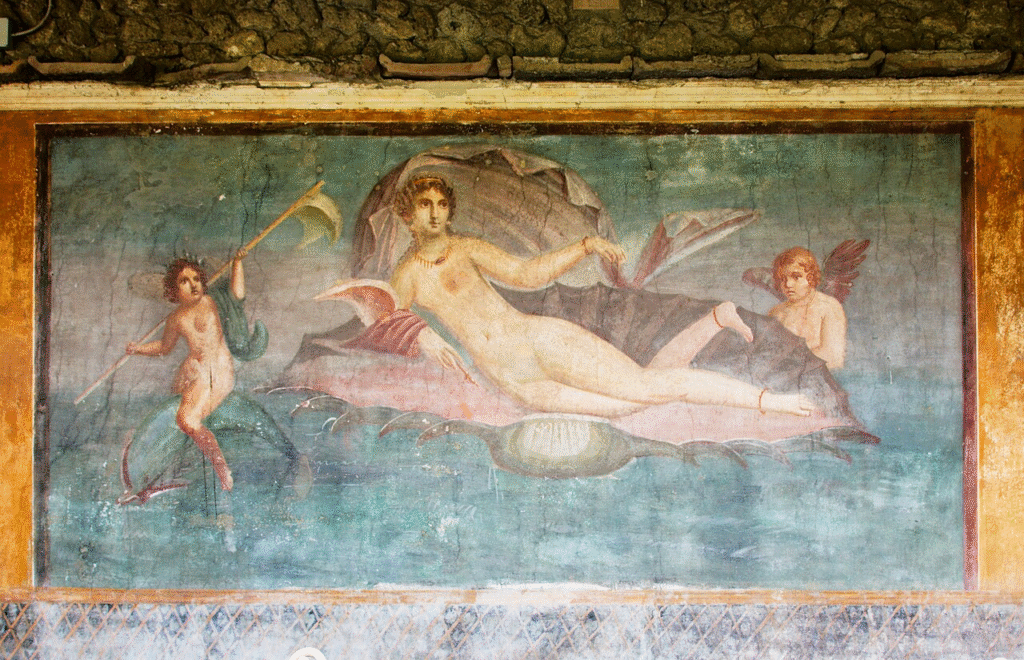

Venus in the Shell (House of Venus in the Shell)

Rising from foaming waves in a scallop shell, Venus Anadyomene shimmers in pinks and blues, her lithe body twisting gracefully as nymphs assist with a cloth, framed by a lush garden trellis in this Fourth Style idyll. Inspired by Greek depictions of the goddess’s birth from sea foam, the scene evokes themes of love, fertility, and renewal, tailored to Roman worship of Venus as patron of Pompeii’s founder. The House of Venus in the Shell, named for this very painting, used it to adorn a peristyle or viridarium, turning an inner courtyard into a romantic sanctuary that blurred indoor and outdoor realms for relaxation and social gatherings.

Its romantic allure and pristine condition make it one of Pompeii’s most photographed works, symbolizing feminine divinity and artistic finesse. Preserved on-site with some elements in Naples, it highlights Fourth Style’s vibrant, illusionistic gardens. Cultural travelers cherish it for illustrating Roman domestic piety and the sensual side of mythology.

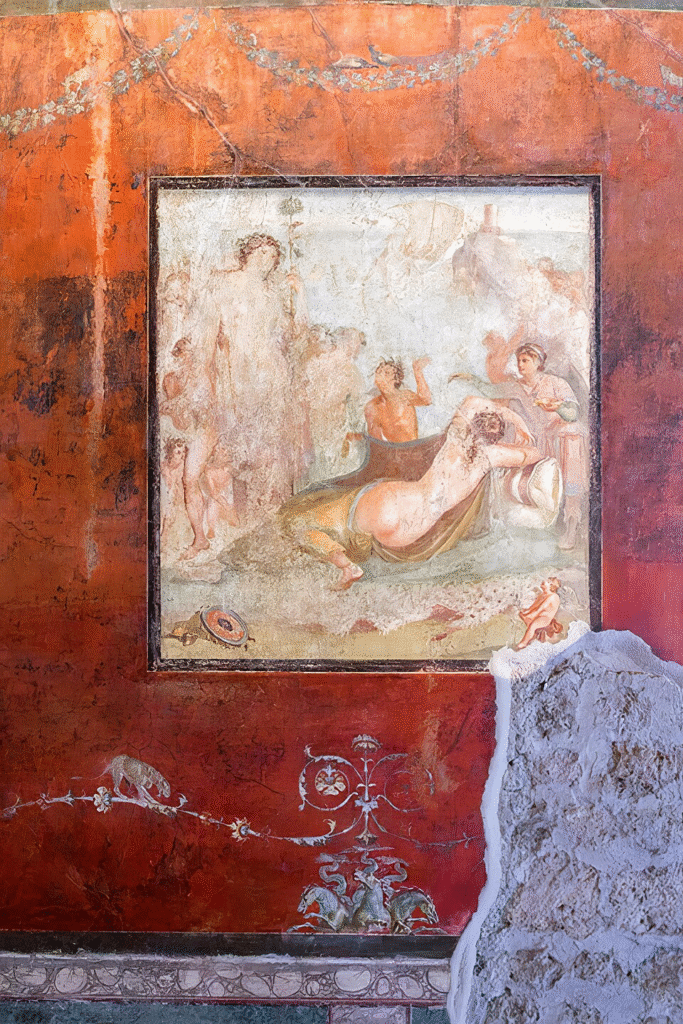

Ixion Room Frescoes (House of the Vettii)

Mythological drama unfolds in the Ixion Room of the House of the Vettii, where crimson walls host punishing scenes: Ixion bound to a fiery wheel by Mercury, Daedalus crafting the Cretan bull for Pasiphae’s illicit passion, and the infant Hercules throttling serpents in his cradle, all in Fourth Style’s intricate panels with architectural frames and vivid contrasts. These tales warned of hubris and divine retribution while celebrating heroic lineage, reflecting the Vettii brothers’ freedman status and aspiration to elite culture through learned decoration. The room, part of a luxurious peristyle villa, served as a triclinium for intimate dinners, immersing guests in stories that sparked conversation and displayed the owners’ wealth post-earthquake restoration.

The House of the Vettii ranks among Pompeii’s top attractions for its cohesive fresco program, with originals largely in situ drawing art pilgrims. Unearthed in the 19th century, these works showcase narrative complexity and color mastery, revealing Roman engagement with Greek myths to navigate social ascent. They remain iconic for blending education with opulence.

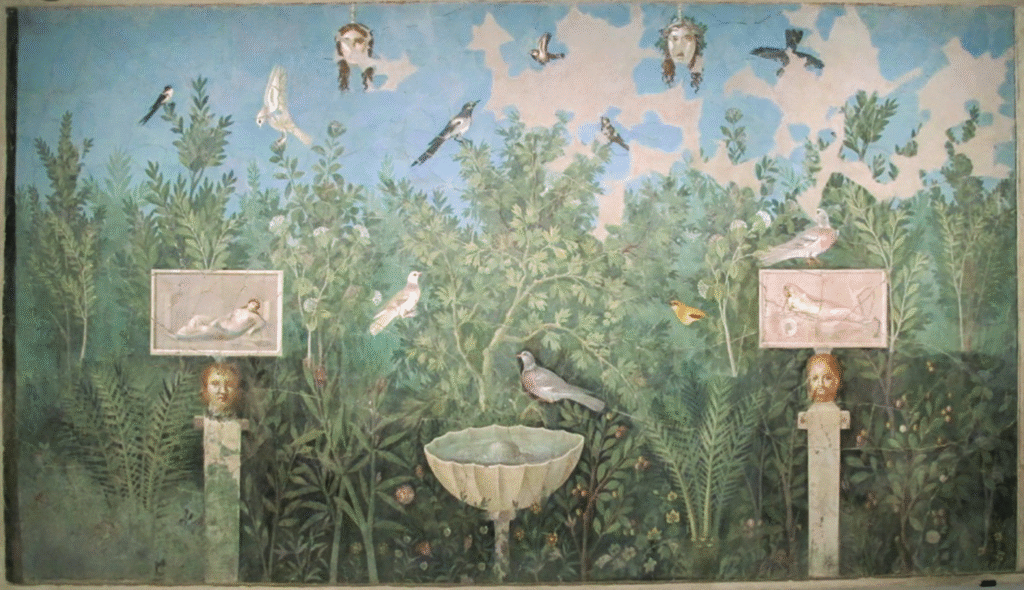

Garden Frescoes (House of the Golden Bracelet and others)

Birds flit among blooming roses and fountains in the Garden Frescoes, where trompe-l’œil effects make walls dissolve into verdant paradises, rendered in greens, pinks, and blues of the Fourth Style to mimic nature’s bounty. These illusionistic scenes, featuring exotic birds, fruits, and fountains, symbolized abundance and the Roman ideal of otium, leisure in harmony with nature, often invoking Bacchus or garden deities for prosperity. In the House of the Golden Bracelet and similar viridaria, they transformed courtyards into serene retreats, enhancing al fresco meals and family life while masking urban constraints.

Their vivid realism captivates, exemplifying Pompeian ingenuity in domestic escape; many originals remain on-site, with fragments in Naples. Visited widely, they illuminate class-based leisure and environmental artistry. For enthusiasts, these frescoes capture the sensory joy of ancient gardens.

Still Life with Peaches and Glass Jar (House of the Stags, or similar)

Peaches gleam with dew-like texture beside a translucent glass jar in this still life, where shadows play across surfaces in hyper-realistic detail, using Fourth Style’s subtle shading to fool the eye into tasting the fruit. Known as xenia, gifts for guests, these compositions celebrated hospitality with everyday abundance, drawing from Greek still-life traditions adapted to Roman domesticity. Likely in the House of the Stags’ atrium or similar entry space, it greeted visitors with humble elegance, reflecting middle-class values amid Pompeii’s commercial vibrancy.

A pinnacle of ancient trompe-l’œil, it astounds for its technical prowess, preserved in Naples as a genre exemplar. It humanizes Roman art, showing mundane beauty’s elevation.

Pompeian frescoes endure as bridges to antiquity, their influence echoing in Renaissance masters like Raphael and modern decorators seeking timeless allure. Preservation efforts, from 18th-century digs to today’s restorations, safeguard these windows into Roman ingenuity against time’s erosion. They fascinate still because they pulse with life: gods, riots, lovers, and fruits frozen in ash, inviting us to ponder the universals of human expression. In an age of fleeting digital art, Pompeii’s walls remind us of creation’s lasting power.

Deeper Dive into Pompeii’s Masterpieces

For the discerning traveler seeking more than surface allure, Pompeii’s frescoes invite scholarly pursuit and immersive exploration. These ancient walls, preserved by Vesuvius’s wrath, reveal layers of Roman ingenuity, from Dionysiac rites to domestic portraiture. Delve further with these curated resources, blending official guides, expert analyses, and practical visitation tips to enrich your journey to the ruins or Naples’ collections.

- Official Pompeii Sites Guide: An essential companion for navigating excavations, with maps, histories, and highlights of key houses like the Vettii and Faun. Ideal for planning self-guided tours. https://pompeiisites.org/en/

- Pompeii Art Guide: Frescoes and Mosaics: A vivid overview of scandalous and mythic works, including the Villa of the Mysteries’ initiation scenes and the Alexander Mosaic. Updated for 2025 discoveries, perfect for art historians. https://walksofitaly.com/blog/art-culture/pompeii-art-frescoes-mosaics/

- National Archaeological Museum of Naples (MANN) Frescoes Collection: Explore originals like the Riot in the Amphitheatre and still lifes, with exhibits on Fourth Style techniques and contexts. Book timed entries to avoid crowds. https://www.museoarcheologiconapoli.it/en/frescoes/

- Alexander Mosaic Analysis: Detailed study of the House of the Faun’s epic, including its Hellenistic roots and modern replicas at the site. Complements visits with historical depth. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/roman/early-empire/a/alexander-mosaic-from-the-house-of-the-faun-pompeii

- Villa of the Mysteries Interpretations: Scholarly essays on the frieze’s enigmatic rituals, from Bacchic cults to bridal initiations. Pair with virtual tours for remote contemplation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Villa_of_the_Mysteries

- 20 Iconic Pompeii Frescoes Gallery: High-resolution images and contexts for works like the Three Graces and Garden scenes, emphasizing preservation techniques. A visual feast for enthusiasts. https://www.worldhistory.org/collection/163/20-frescoes-from-pompeii/

If our work has inspired you, helped you grow, or simply brought a little warmth to your day, consider supporting Thalysia.com with a small donation. Your contribution helps us continue exploring ancient landscapes, documenting local traditions, and celebrating the art of living well.