In the swirling tides of the fifth-century Mediterranean, few tales unfold with the dramatic flair of the Vandals, those Germanic wanderers who carved out a sun-drenched kingdom along North Africa’s storied shores. From the bustling ports of Carthage to the wind-swept coasts of Tunisia and Algeria, their rule for nearly a century wove together threads of conquest, cultural fusion, and spiritual strife, transforming a Roman legacy into something vividly new. Imagine the clash of northern vigor against ancient olive groves and azure waves; this was no mere invasion, but a chapter of reinvention that echoes through the ruins travelers explore today, inviting us to ponder the fluidity of identity in a world on the brink of change.

The odyssey began in 429 AD, when some 80,000 Vandals, driven by necessity and led by the cunning Geiseric, crossed from Hispania into the fertile crescent of North Africa. These were not mindless hordes, but a people in search of enduring roots, pressing eastward through provinces that would become modern Algeria and Tunisia, their footsteps marking a shift in the region’s destiny. The Western Roman Empire, beleaguered on all fronts, first sought peace through a 435 treaty, ceding Numidia and Mauretania as allied territories, yet Geiseric’s vision stretched further, toward the heart of power. On October 19, 439, his forces slipped into Carthage under cover of distraction, as the city’s elite gathered at the hippodrome for chariot races; the city’s fall sent ripples across the Mediterranean, turning the ancient Phoenician port, once Rome’s granary jewel, into the throne of a nascent empire.

From Carthage’s marble forums, Geiseric proclaimed himself King of the Vandals and Alans, honoring his steppe-born allies, and swiftly built a seafaring domain that commanded the western sea’s vital arteries. By the 440s, his fleets had claimed Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica, Malta, and the Balearic Islands, choking Roman trade in grain and goods, a stranglehold that hastened the empire’s economic unraveling. The 455 sack of Rome, often romanticized in lore, proved their audacious reach, though it spared the city greater ruin; in North Africa, this maritime prowess funded a realm that thrived on the land’s bountiful harvests, blending Germanic resolve with the enduring pulse of Mediterranean commerce.

The kingdom’s longevity, spanning 99 years amid the chaos of falling empires, speaks to its shrewd governance, outpacing many Germanic peers. Geiseric’s death in 477 ushered in a fragile détente with the Eastern Roman Empire, where diplomacy masked simmering religious divides, and the Vandals’ hold on Africa’s agricultural riches sustained their independence. Yet imperial eyes from Constantinople never wavered. In 533, Emperor Justinian unleashed General Belisarius on a lightning campaign; at the Battle of Tricamarum that December, Vandal lines shattered with the fall of commander Tzazo, leading King Gelimer to yield after a grueling siege at Mount Pappua in 534. North Africa folded back into Byzantine embrace, its Vandal rulers scattered or absorbed, leaving behind a landscape where Roman roads and aqueducts whispered of transitions yet to come.

At the core of Vandal life pulsed a profound religious schism, one that colored their legacy in the annals of memory. Adherents of Arian Christianity, which positioned Christ as subordinate to the Father, the Vandals clashed irreconcilably with the Nicene Catholic majority they governed, a tension that ignited policies of exclusion from their 429 arrival. Geiseric confiscated basilicas, banished defiant bishops, and elevated Arian clergy, forging a divide sharper than in other Germanic lands where faiths often mingled more gently. His son Hunaric, ruling from 477 to 484, escalated the fervor, exiling bishops to desert outposts, seizing churches, and meting out torture or death to resisters; Bishop Eugenius of Carthage, paraded in mockery before his exile, became a symbol of this ordeal, his story etched vividly by chronicler Victor of Vita, whose words would shape centuries of judgment.

Scholars now see these measures as dual-edged, serving not just doctrinal zeal but political cunning, viewing the Catholic clergy as a Byzantine-aligned threat and Arianism as a bulwark for Vandal cohesion amid a Roman sea. This strife, intense yet contained, underscores the kingdom’s unique texture, a realm where faith was both sword and shield in the forge of power.

Beyond the altars, Vandal society bloomed in unexpected harmony, defying tales of barbaric rupture. Archaeological whispers and texts alike reveal intermingling: Vandal nobles in Roman villas, adopting togas and symposia, while locals embraced Germanic flair in jewelry and banquets, crafting a hybrid world far richer than conqueror-and-conquered divides suggest. Far from razing culture, the Vandals nurtured it; late antique learning thrived under their patronage, with scholars penning works that bridged old and new, and historians like Averil Cameron argue that for many North Africans, Vandal oversight might have eased the yoke of absentee Roman landlords, fostering a subtle welcome amid the upheaval.

Carthage’s digs paint this evolution in earth and stone: walls weathered yet mended, forums repurposed for Vandal needs, all layered within the city’s Punic-Roman-Byzantine tapestry, a testament to continuity over catastrophe. The urban hum persisted, alive with markets and mosaics, as the kingdom’s era folded into the next without erasing the vibrant Roman African soul.

Sovereignty gleamed most tangibly in the Vandals’ coins, struck fresh in Carthage from 439 onward, emblems of their economic grip that numismatists now dissect for insights into trade and rule. These bronze nummi and gold solidi, bearing Geiseric’s mark, journeyed afar, unearthed in Egyptian sands and Sicilian hoards, threading networks that outlived the realm; post-534, Byzantine mints in the same halls perpetuated the flow, a quiet nod to enduring commerce. Adapting Roman bureaucracy, the Vandals taxed fields and harbors with efficiency, their mastery of grain fleets not only enriching Carthage but delivering a fatal strain to Western Rome’s coffers, accelerating its twilight.

In the end, the Vandal interlude stands as a luminous bridge in North Africa’s saga, linking Roman splendor to Byzantine renewal through preserved institutions and cityscapes that eased the 534 handover. Ethnic traces faded swiftly, their Germanic tongue and customs dissolving into the multicultural mosaic, leaving scant “Vandal” artifacts, mostly Roman-infused hybrids that speak of rapid assimilation. The very word “vandal,” twisted in later tongues to mean destroyer, betrays more about medieval biases than Geiseric’s measured reign. Today, wanderers tracing Carthage’s forums or sifting numismatic troves encounter a nuanced truth: this was no alien blight, but a vibrant synthesis, where northern blades tempered in African light forged a fleeting yet indelible mark on the Mediterranean’s endless story.

Essential Sites for Vandal History Enthusiasts

For those drawn to the Vandals’ intriguing chapter in North Africa’s story, a journey through key sites reveals layers of cultural fusion and historical drama. Focus on Tunisia and Algeria, where the kingdom’s remnants blend with Roman, Punic, and Byzantine echoes, offering a tangible sense of Geiseric’s maritime realm. These spots reward the curious traveler with ruins, museums, and landscapes that whisper of fifth-century transformations.

Carthage: The Heart of the Vandal Empire

Start in Carthage, the opulent capital that Geiseric claimed in 439, transforming it into the nexus of his seafaring domain. Wander the Antonine Baths, vast marble structures still evoking the city’s Roman splendor, now overlaid with Vandal-era adaptations visible in restored mosaics and urban layouts. The Carthage National Museum houses artifacts like coins and inscriptions that illuminate Arian influences and hybrid artistry, providing a direct link to the kingdom’s administrative vibrancy.

Climb Byrsa Hill for panoramic views of the ancient port, where Vandal fleets once dominated Mediterranean trade; nearby, the excavated amphitheater hints at the 439 conquest’s chaotic dawn. This site’s stratified ruins, from Punic origins to Vandal layers, make it an ideal anchor for understanding cultural synthesis, with guided tours often weaving in Victor of Vita’s persecution tales for added depth.

Utica: Echoes of Early Conquests

Just west of Carthage lies Utica, a coastal gem where Vandal forces made initial footholds in 429, securing their advance into the fertile plains. Explore the Roman theater and forum, preserved amid olive groves, to sense the transition from Roman outpost to Vandal stronghold; subtle archaeological traces, like altered fortifications, speak to the invaders’ strategic overlays. The site’s museum displays numismatic finds, including Vandal bronze nummi that circulated far beyond Africa, highlighting economic ties.

Utica’s quiet harbors and hilltop acropolis offer serene reflection on the migrants’ odyssey, with spring wildflowers framing ruins that evoke the kingdom’s agricultural mastery. Pair a visit with nearby Dougga for broader Roman context, but Utica’s understated Vandal imprints reward patient explorers seeking the era’s fluid borders.

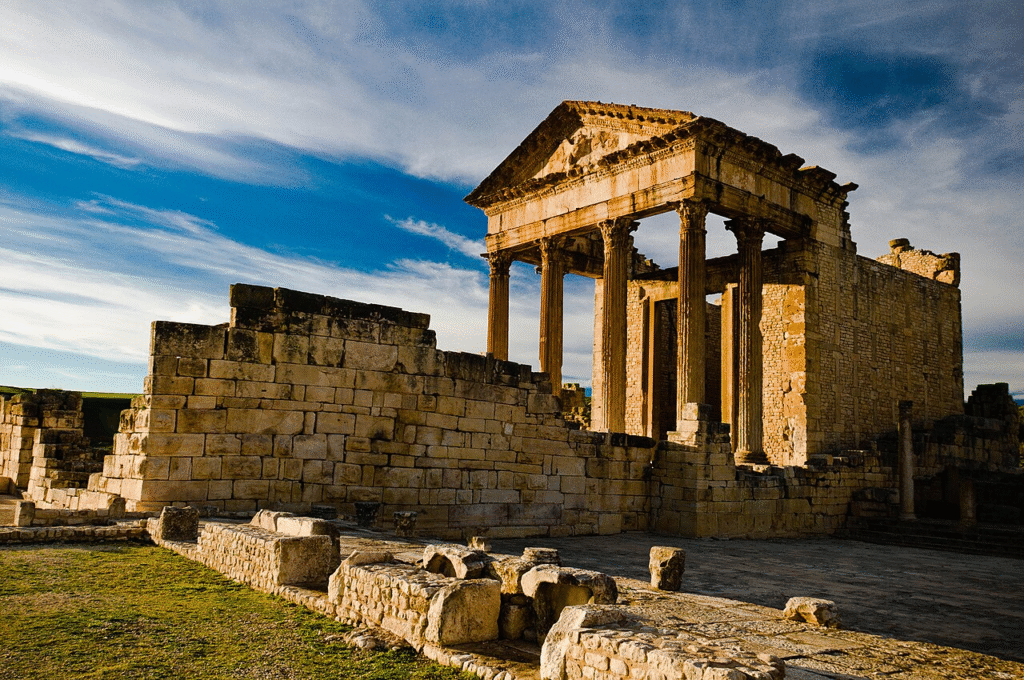

Dougga: Administrative Strongholds and Rural Life

Venture inland to Dougga, a UNESCO jewel in Tunisia’s hills, representing the Vandal administration’s reach into Numidia’s heartlands granted by the 435 treaty. This impeccably preserved Roman city, with its capitol, temples, and aqueducts, continued thriving under Vandal rule, as evidenced by minimal disruption in the archaeological record and ongoing grain production. Ascend the theater for views of terraced fields that fed the empire, imagining Huneric’s policies shaping local governance.

The site’s baths and villas illustrate elite intermingling, where Vandal nobles adopted Roman customs, a theme echoed in nearby museums’ displays of hybrid pottery. Dougga’s isolation from coastal raids makes it a peaceful counterpoint to Carthage, perfect for pondering the kingdom’s 99-year stability amid religious tensions.

Teboursouk and Simitthus: Battlefields and Persecution Sites

For the drama of the endgame, head to Teboursouk in northern Tunisia, near the 533 Battle of Tricamarum where Belisarius shattered Vandal lines upon Tzazo’s fall. Though the exact field eludes precise mapping, local Roman ruins and Byzantine-era churches mark the path of reconquest, with hikes revealing the rugged terrain that tested Gelimer’s defenses. Nearby, the mausoleum of the Numidian kings adds a layer of pre-Roman antiquity, contextualizing Vandal integration.

In eastern Algeria, Simitthus (now Sbeitla in Tunisia, but linked to broader Mauretania) offers insights into Catholic strongholds targeted by Arian policies; its basilicas, like those seized under Geiseric, stand as testaments to faith’s fiery currents, with inscriptions detailing episcopal exiles. These sites, amid Saharan fringes, blend history with stark beauty, ideal for travelers tracing persecution narratives through Victor of Vita’s lens.

Tips for an Immersive Journey

Travel in spring or fall to avoid summer heat, basing in Tunis for easy access to Carthage and Utica, then renting a car for inland spots like Dougga. Engage local guides versed in late antiquity for nuanced stories beyond standard tours, and visit the Bardo National Museum in Tunis for Vandal coins and mosaics that tie sites together. This itinerary not only revives the Vandals’ bridge between worlds but invites reflection on North Africa’s enduring cultural weave.

Header image: Leptis Magna, Joe Pyrek from Richmond, Va, USA.

If our work has inspired you, helped you grow, or simply brought a little warmth to your day, consider supporting Thalysia.com with a small donation. Your contribution helps us continue exploring ancient landscapes, documenting local traditions, and celebrating the art of living well.