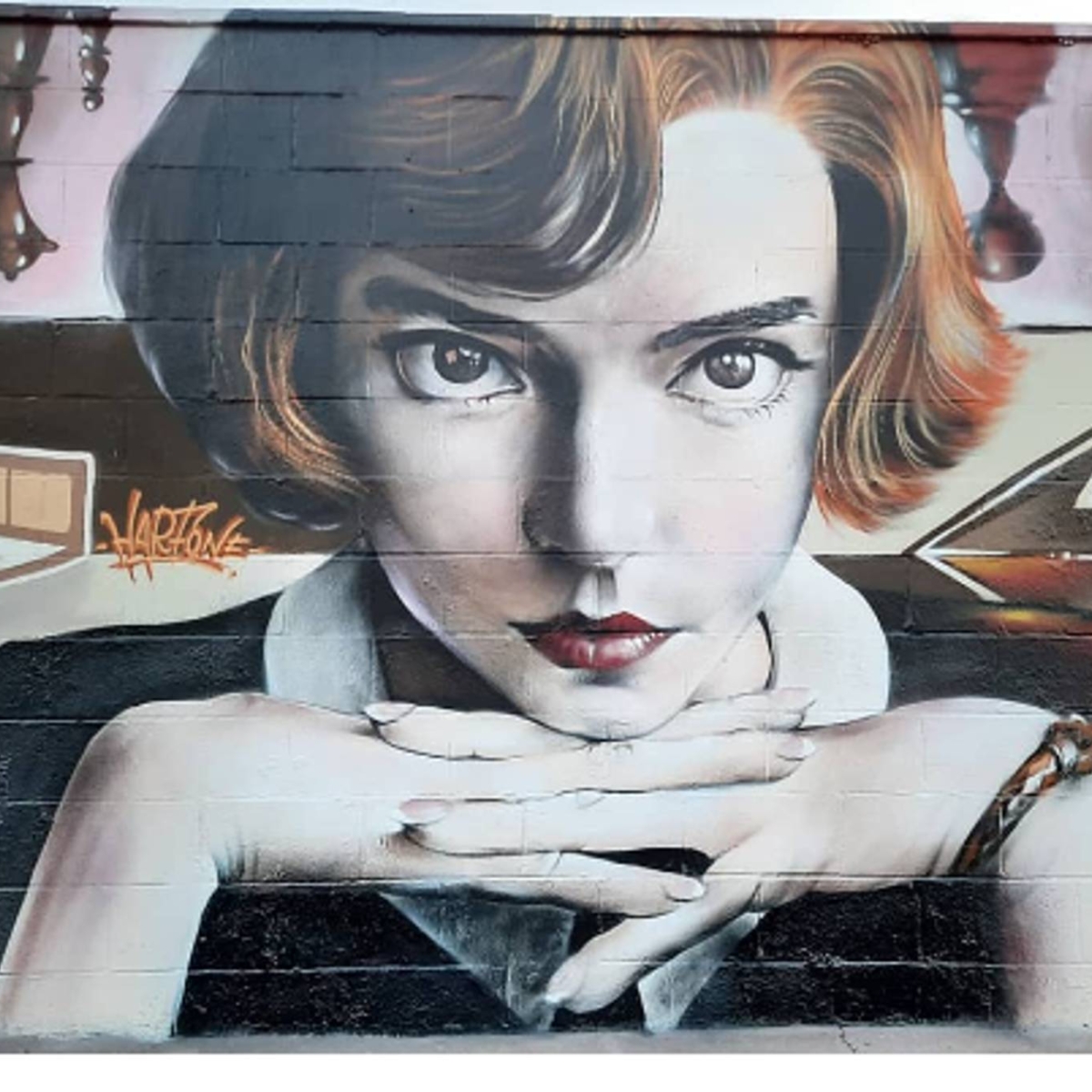

The narrow streets of the Mediterranean have always been galleries. Long before museums claimed sacred art as their territory, devotion lived on plaster and stone, painted onto the weathered facades of neighborhood shrines and tucked into the corners of alleyways. From the gold-leafed iconostasis of Byzantine churches to the spray-painted prophets of modern Athens, the visual language of faith has never stopped evolving. What we see today in the graffiti-covered walls of Naples or the towering murals of Barcelona is not a break from tradition but its continuation. Sacred art has simply changed its medium, its audience, and sometimes its gods.

To walk through a Mediterranean city is to witness centuries of devotion layered one atop another. The aesthetic vocabulary remains remarkably consistent: halos become aureoles of light, saints transform into revolutionaries, and the Virgin Mary’s robes echo in the flowing garments of anonymous street figures. These images are not mere decoration. They are prayers made visible, declarations of identity, and acts of resistance. They speak to a deep-seated need to mark public space with meaning, to claim the street as a site of the sacred.

From Icons to Wall Shrines: The Sacred in Public Space

The Mediterranean has always understood that holiness need not be confined. While Northern Europe built its towering cathedrals to house the divine, Southern cities scattered their saints across every available surface. In Greece, roadside proskinitaria (small shrines) dot the highways, their interiors lined with icons and flickering oil lamps. In Italy, edicole sacre (wall shrines) punctuate the urban fabric of Naples and Palermo, offering passersby a moment of communion with a favored saint. These are not grand gestures but intimate ones, woven into the daily rhythms of neighborhood life.

The tradition extends back to antiquity. Romans placed lararia (household shrines) at thresholds and crossroads, seeking protection from the spirits that governed doorways and journeys. Early Christians adapted this impulse, painting images of Christ and the apostles in the catacombs of Rome, creating an underground network of devotional art that would eventually emerge into the light of Byzantine splendor. By the medieval period, ex-voto paintings, small devotional works commissioned by individuals in gratitude for answered prayers, began appearing in churches and public spaces throughout the Catholic Mediterranean.

What makes these traditions so enduring is their accessibility. Unlike the formal altarpieces locked behind church doors, street shrines belong to everyone. A Neapolitan grandmother can light a candle to San Gennaro on her way to market. An Athenian taxi driver can cross himself before an icon of the Virgin mounted at a busy intersection. The sacred is not distant or hierarchical; it is woven into the texture of daily survival.

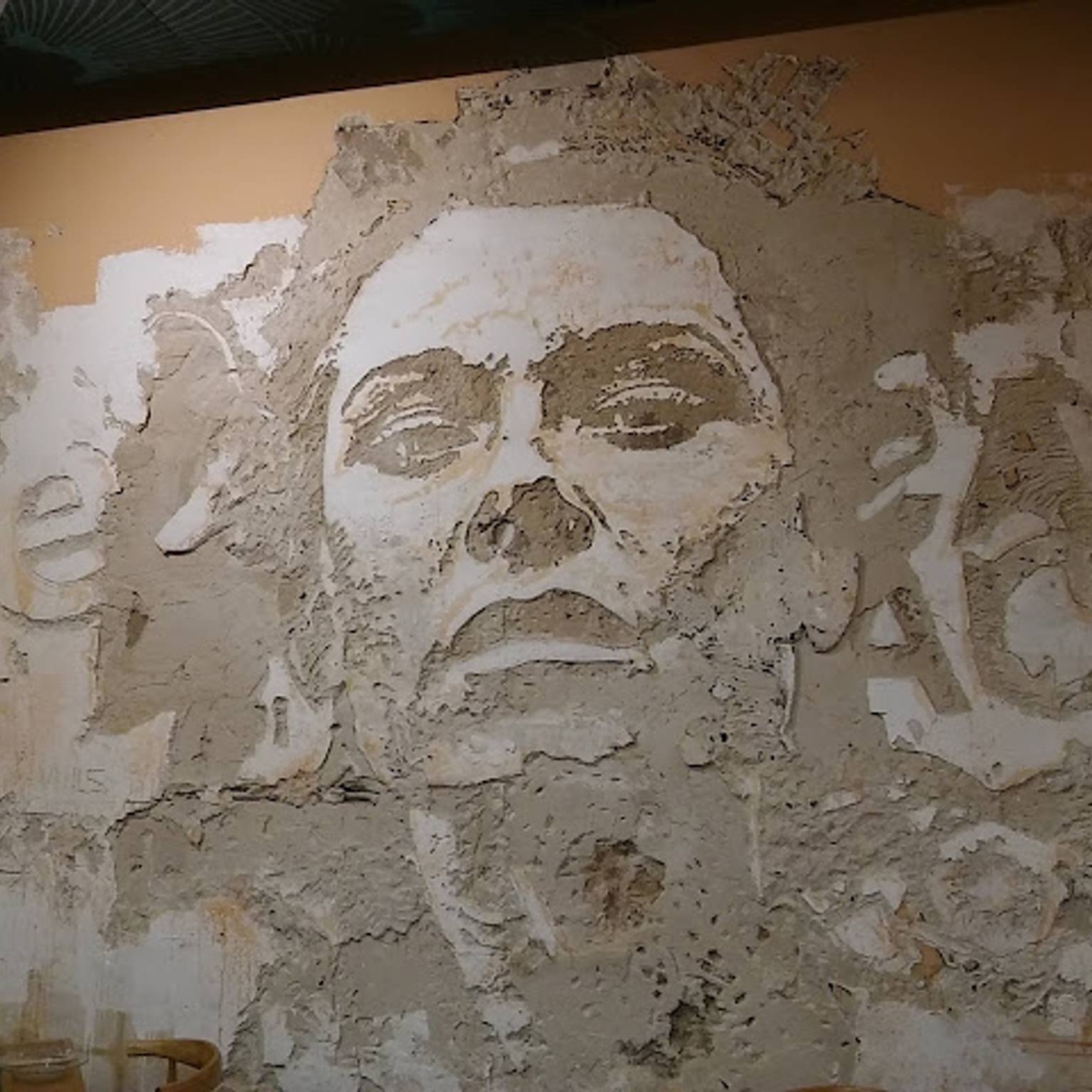

This democratic approach to devotion created an aesthetic that would prove remarkably adaptable. The flat, frontal compositions of Byzantine icons, with their stylized figures and symbolic use of gold, established a visual grammar that transcended religious boundaries. Moorish artisans in Andalusia borrowed geometric patterns and calligraphic flourishes, integrating them into architectural ornamentation that blurred the line between the sacred and the decorative. Jewish communities in the Sephardic diaspora carried their own traditions of illuminated manuscripts and symbolic imagery, adding another layer to the Mediterranean visual vocabulary.

By the time street art began emerging as a distinct form in the late twentieth century, the Mediterranean had already spent millennia treating its walls as canvases for collective devotion. The shift from saint to street prophet was less radical than it might appear.

Murals and the Language of Collective Memory

The modern mural movement in Mediterranean cities owes as much to political upheaval as to artistic innovation. In the 1960s and 1970s, as student protests, labor strikes, and anti-fascist movements swept through Southern Europe, activists discovered that walls could be weapons. Murals became declarations, manifestos painted large enough to be seen from across a piazza. In Barcelona, artists reclaimed the city’s surfaces after decades of Francoist censorship, covering them with Catalan symbols and scenes of resistance. In Athens, the economic crisis of the 2010s triggered an explosion of street art that transformed entire neighborhoods into open-air galleries of grief and defiance.

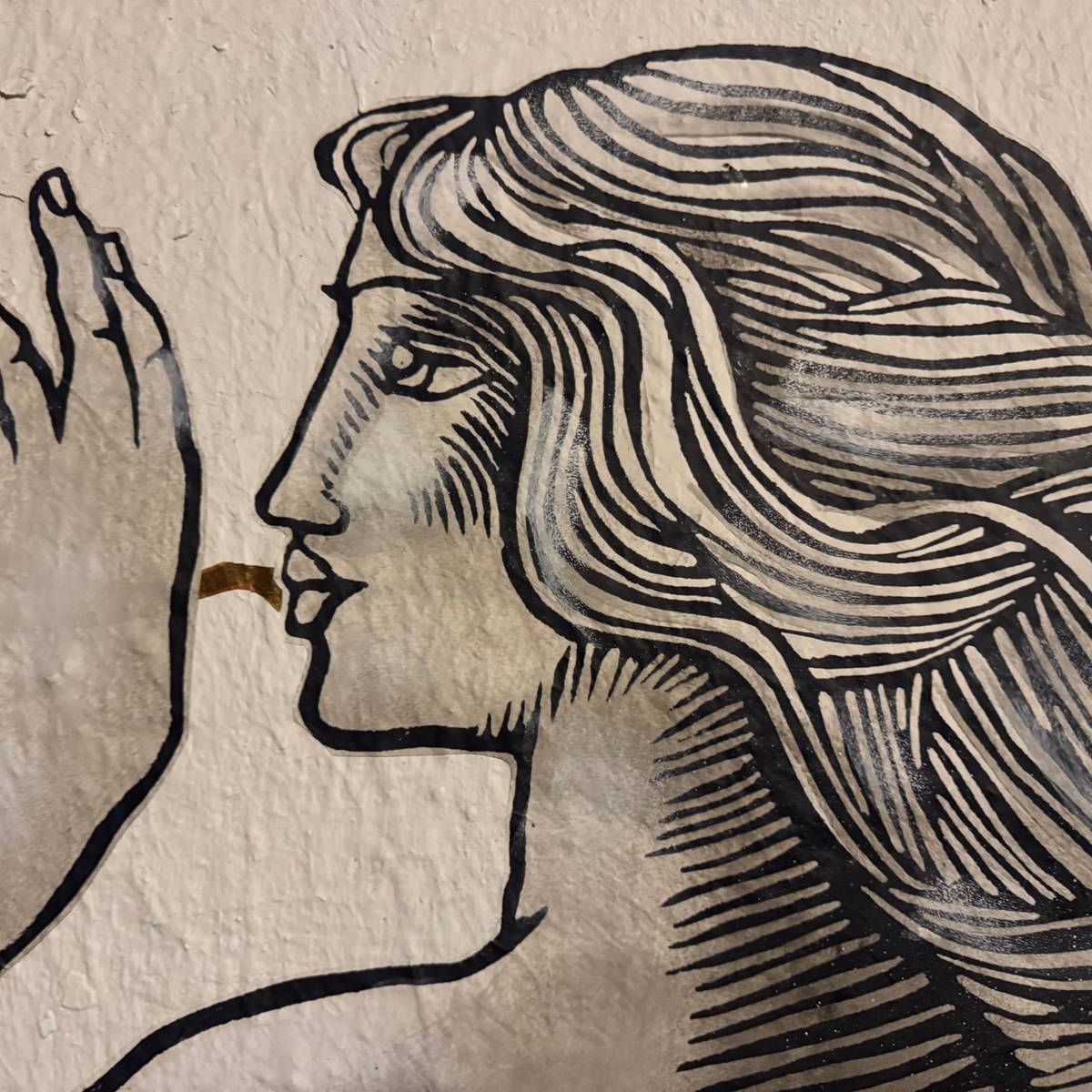

What distinguishes Mediterranean muralism from its counterparts elsewhere is its deep engagement with religious iconography. Artists did not abandon the visual language of faith; they repurposed it. The composition of a traditional altarpiece, with its central figure surrounded by subsidiary scenes, reappears in contemporary murals that place a modern hero (a murdered activist, a drowned refugee, a labor organizer) at the center of a secular hagiography. The suffering Christ becomes the suffering worker. The martyred saint becomes the martyred protester.

In Palermo, murals commemorating Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino, the anti-mafia judges assassinated in 1992, draw explicitly on Catholic visual traditions. The judges are depicted with serene, almost beatific expressions, their figures often backlit or haloed in ways that recall Renaissance painting. The message is clear: these men are modern saints, their sacrifice sacred, their memory a form of ongoing devotion. Locals bring flowers to the walls, touching the painted faces as they might touch a church relic.

Naples takes this synthesis even further. The city’s quartieri (neighborhoods) are dense with murals that blend sacred and secular, ancient and contemporary. Maradona, the Argentine footballer who became a god in Naples during the 1980s, appears in murals that mimic the compositional structure of Byzantine icons, his image surrounded by smaller vignettes of his greatest moments. The irony is intentional, but so is the reverence. In a city where economic marginalization has been the norm for centuries, football provided transcendence, and Maradona became a genuinely religious figure. The murals are not parody; they are theology.

Athens presents a different evolution. The city’s exarcheia neighborhood, long a haven for anarchists and artists, features murals that engage critically with Orthodox imagery. Figures resembling Byzantine saints hold Molotov cocktails instead of palm branches. The Virgin Mary appears as a gas-masked protester. These images are provocations, but they also reveal how deeply ingrained religious aesthetics are in the Greek visual imagination. Even in rejection, the iconographic language persists, because it is the most powerful visual vocabulary available.

What unites these disparate examples is a shared understanding: the mural is not simply art for art’s sake. It is communal memory made permanent, or at least semi-permanent, until the next layer of paint covers it. Like the ex-voto paintings of earlier centuries, murals tell stories of suffering, survival, and hope. They mark territory, claim identity, and invoke protection. They are, in the most fundamental sense, devotional acts.

Graffiti as the New Folk Devotion

If murals are the altarpieces of the street, graffiti is its litany, its repeated prayers. The distinction between the two is not always clear, but graffiti tends toward the fragmentary, the quick, the insurgent. It is less about creating a coherent narrative and more about marking presence. A tag sprayed on a wall declares: I was here. I exist. In Mediterranean cities where unemployment, displacement, and political disenfranchisement leave many feeling invisible, that declaration carries weight.

Yet graffiti in the Mediterranean is rarely as nihilistic as it is sometimes portrayed. Scratch the surface, and you find traces of the old devotional impulse. In Barcelona’s El Raval district, graffiti artists paint guardian figures at strategic intersections, unofficial protectors of the neighborhood’s immigrant communities. The figures often incorporate elements of Islamic geometric design, Amazigh symbols, and Catholic imagery, creating syncretic icons for a syncretic population. These are not advertisements or acts of vandalism; they are blessings.

Naples offers perhaps the most striking example of graffiti as folk devotion. The city’s murale (murals) often begin as graffiti, unauthorized paintings that gradually gain community acceptance and protection. A small tag honoring a deceased friend becomes, over time, a neighborhood shrine, with passersby adding their own tributes, flowers, and candles. The line between graffiti and sacred art dissolves entirely. The street becomes a palimpsest, each layer of paint a prayer, each overpaint an act of consecration or erasure.

In Athens, graffiti artists have adopted the ancient practice of apotropaic imagery, signs meant to ward off evil. Eyes, hands, and protective symbols appear on shuttered storefronts and crumbling neoclassical buildings, unconscious echoes of the mati (evil eye) amulets that dangle from rearview mirrors across Greece. The artists may not think of themselves as continuing a tradition, but they are. The impulse to protect space through visual marking is as old as humanity, and graffiti is simply its latest iteration.

What makes contemporary Mediterranean graffiti particularly compelling is its refusal to choose between the sacred and the profane. A single wall in Palermo might feature a crude tag, a political slogan, a beautifully rendered portrait of a local saint, and an obscene joke, all layered together. This is not chaos; it is the natural state of Mediterranean public space, where the sacred has never been separate from the everyday. The same wall that holds a shrine to the Madonna might also advertise a butcher shop and bear the scars of old bullet holes from a long-ago war. Devotion, commerce, and violence coexist because life is not compartmentalized.

This layering also represents a kind of democratization. Anyone with a can of spray paint can add to the ongoing conversation. The hierarchy of church-sanctioned art, where only trained painters could depict the divine, has given way to a free-for-all where legitimacy comes from community response rather than institutional approval. If a piece of graffiti resonates, it stays. If it offends or bores, it gets painted over. The street is a ruthless curator.

There is something profoundly hopeful in this. At a time when traditional religious institutions struggle with declining attendance and relevance, the streets are alive with visual theology. Young people who might never enter a church still create images that grapple with suffering, justice, memory, and transcendence. They may not use the language of religion, but they are engaged in fundamentally religious acts: making meaning, claiming space, invoking the sacred.

The Eternal Canvas

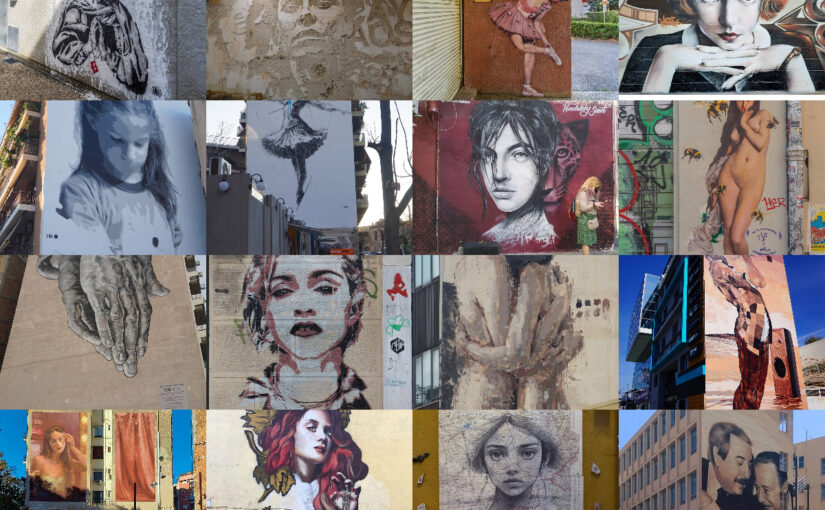

The Mediterranean has always been a place of layers. Civilizations rise and fall, languages blend and diverge, and the stones themselves bear the marks of countless hands. What we call graffiti today is only the latest addition to a palimpsest thousands of years deep. Beneath the spray paint are the murals. Beneath the murals are the icons. Beneath the icons are the Roman frescoes, the Greek votive reliefs, the Phoenician carvings. Each generation adds its voice to the chorus.

To dismiss contemporary street art as vandalism or to romanticize it as pure rebellion is to miss the point. The walls of Athens, Naples, Palermo, and Barcelona are doing what Mediterranean walls have always done: bearing witness. They carry forward the ancient conviction that the sacred belongs in public, that devotion should be visible, and that beauty can be a form of resistance. The faces may change, the gods may multiply or disappear, but the impulse remains. We paint because we must, because the wall demands it, because silence is unbearable.

Stand on any street corner in the Mediterranean long enough, and you will see someone pause before an image. It might be an old woman crossing herself before a faded icon, or a teenager studying a new mural with quiet intensity, or a tourist snapping a photo of graffiti they don’t quite understand. In that moment, all are participating in the same ritual, the same ancient conversation between image and observer, between the street and the soul. The layers of devotion continue to accumulate, one spray can, one brushstroke, one prayer at a time.

Street Art Cities is a global online platform and mobile app dedicated to mapping, documenting, and promoting street art worldwide. Launched in 2016 to help enthusiasts track urban artworks, it has grown into the largest community-driven database, featuring over 65,000 pieces across more than 1,800 cities in 100+ countries.