In the sun-drenched realms of Victorian neoclassicism, John William Godward crafted visions that transport viewers to an idealized ancient Mediterranean world, where marble gleams under eternal light and draped figures embody serene elegance. His 1908 oil painting “Athenais” stands as a captivating example, drawing on the myths and aesthetics of classical Greece to evoke a sense of languid beauty amid opulent surroundings. This work, now housed in a private collection, measures about 101 by 61 centimeters and captures a moment of quiet introspection that resonates with the artistic traditions of the Mediterranean’s storied past.

Godward, born in 1861 in London to a middle-class family, immersed himself in the neoclassical revival that flourished in England during the late 19th century. He trained under the influence of masters like Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, whose own paintings romanticized Roman and Greek antiquity with meticulous detail and vibrant hues. By 1887, Godward was exhibiting at the Royal Academy, and his style quickly gained notice for blending archaeological precision with poetic sensuality. He moved to Italy in 1912, settling near Rome’s Villa Borghese to surround himself with authentic classical artifacts, which informed works like “Athenais.” Yet, as modernism swept through the art world in the early 20th century, his traditional approach fell from favor, leading to personal struggles that ended tragically with his suicide in 1922 at age 61. Despite this, Godward’s legacy endures, with pieces like “Dolce far Niente” fetching high prices at auctions today, proving the lasting appeal of his Mediterranean-inspired reveries.

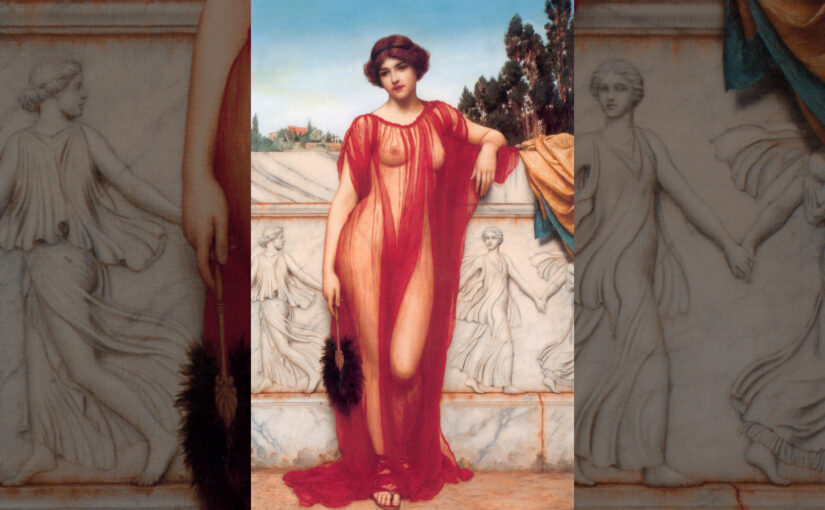

At the heart of “Athenais” lies a young woman, her form a harmonious blend of vulnerability and poise, leaning against a cool marble wall adorned with intricate bas-relief carvings of mythical figures. She wears a sheer red garment that clings softly to her skin, its translucent folds revealing the subtle curves of her body in a way that suggests both intimacy and restraint. The fabric’s crimson glow catches an imagined sunlight, contrasting sharply with the white stone behind her, which features classical motifs like garlands and draped deities that nod to ancient Greek temples. Her dark hair cascades in loose waves, framing a face turned slightly away, eyes downcast in contemplation, as if lost in a private reverie. One hand rests lightly on the marble, fingers tracing its smooth surface, while the other holds the edge of her robe, adding a touch of everyday grace to the scene’s ethereal quality.

This composition masterfully plays with textures that Godward rendered with extraordinary skill, a hallmark of his technique honed through years of study. The marble’s polished sheen appears almost tangible, its veins and carvings evoking the enduring stone of Mediterranean ruins like those at Pompeii or Athens. In opposition, the woman’s skin glows with a warm, lifelike softness, and the diaphanous silk of her dress shimmers as if stirred by a gentle breeze from the Aegean Sea. Such contrasts were Godward’s signature, allowing him to weave a narrative of tactile delight, where the hardness of antiquity meets the fluidity of human form. Critics of his era praised this ability to convey “the feel of contrasting textures, flesh, marble, fur and fabrics,” though some dismissed his subjects as mere “Victorians in togas,” overlooking the depth of his classical inspirations.

The title “Athenais” invites curiosity about its historical roots, drawing from ancient lore tied to the Mediterranean’s mythic heritage. In classical texts, Athenais emerges as a prophetess from Erythrae in Asia Minor, one of the oracles who affirmed Alexander the Great’s divine lineage during his conquests across the Greek world. Strabo and Pausanias mention her as a seer whose visions bridged the mortal and divine, embodying the wisdom of ancient priestesses who communed with gods amid olive groves and sacred springs. Godward likely chose this name to infuse his painting with layers of symbolism, portraying his subject not just as a beauty at rest, but as a modern echo of those enigmatic figures who held sway in the temples of Athena or Apollo. For a Mediterranean blog, this connection feels particularly poignant, linking the canvas to the region’s enduring tapestry of oracles, festivals, and seaside shrines that still inspire contemporary artists and storytellers.

Godward’s choice to depict semi-nude forms in classical settings allowed him to explore sensuality within the bounds of Victorian propriety, a delicate balance that mirrored the era’s fascination with the Mediterranean as a cradle of refined hedonism. “Athenais” exemplifies this, her pose languid yet composed, evoking the quiet moments of ancient life, perhaps after a ritual bath or amid the whispers of a symposium. The background’s bas-relief, possibly depicting scenes from Greek mythology, reinforces this immersion, transporting viewers to a world where philosophy and beauty intertwined under the Mediterranean sun. Unlike the more dramatic narratives of contemporaries like Waterhouse, Godward favored these intimate vignettes, creating a dreamlike escape that appealed to collectors seeking the romance of bygone eras.

In today’s art market, “Athenais” reflects Godward’s resurgence, with reproductions and prints popular among those drawn to neoclassical themes. His works now grace institutions like the Getty Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, underscoring how his visions of ancient grace continue to captivate. For enthusiasts of Mediterranean culture, the painting serves as a portal to the aesthetics of olive-strewn hills and azure seas, reminding us that art’s power lies in its ability to revive the past’s whispers in the present. Godward’s brush not only preserved a fading classical ideal but also wove it into the fabric of modern appreciation, ensuring that figures like Athenais remain eternally poised on the edge of myth and memory.

If our work has inspired you, helped you grow, or simply brought a little warmth to your day, consider supporting Thalysia.com with a small donation. Your contribution helps us continue exploring ancient landscapes, documenting local traditions, and celebrating the art of living well.