The thunderous might of Zeus crashes through the skyscrapers of New York City. Sea gods rise from the waves to claim their half-mortal sons. Ancient monsters lurk in the shadows of modern highways. This is the electrifying realm of Percy Jackson and the Olympians, Rick Riordan’s blockbuster series that has captivated millions since its debut in 2005. With over 180 million copies sold worldwide and adaptations spanning books, films, and now a hit Disney+ show, Percy’s adventures have turned Greek mythology into a gateway for young readers to explore the gods, heroes, and beasts of ancient tales. But how much of this fantastical narrative sticks to the truths of Greek mythology? As a fan diving back into these stories or a newcomer curious about the myths that inspired them, you might wonder if Percy Jackson is a faithful retelling or a bold remix. In this deep dive, we’ll unpack the layers of Percy Jackson myths. We’ll reveal where Riordan honors the essence of ancient Greek stories and where he spins creative threads to fit our contemporary world. Let’s journey from Mount Olympus to Camp Half-Blood and beyond. We’ll trace the threads of truth woven into this modern epic.

The heart of the Percy Jackson series pulses with the Olympian gods. These are immortal powerhouses who ruled the ancient Greek cosmos. In Greek mythology, these twelve deities resided atop Mount Olympus. This was a towering peak in northern Greece that symbolized the pinnacle of divine authority. They embodied natural forces, human virtues, and vices. They often clashed in dramas as messy as any soap opera. Riordan transplants this pantheon to the United States. He crowns the Empire State Building as their new throne room. This is a clever nod to America’s role as a modern hub of global influence. This relocation isn’t just logistical. It underscores how myths evolve with cultures. Consider how the Greeks adapted tales from earlier civilizations.

At the forefront stands Zeus, the sky god and king of the Olympians. In ancient lore, drawn from epics like Homer’s Iliad, Zeus hurls thunderbolts forged by Cyclopes to enforce his will. He punishes oath-breakers and rivals with storms that could level mountains. He’s a figure of unyielding authority. Yet he is prone to jealousy and infidelity. He sires countless heroes while dodging the wrath of his wife, Hera. In Percy Jackson, Zeus retains this stormy temperament as a stern patriarch. He enforces a pact among the “Big Three” gods, which includes himself, Poseidon, and Hades. They agree to avoid fathering more demigods after their chaotic offspring nearly toppled the world in the past. This rule is a Riordan invention. It amplifies the tension. Gods can’t meddle directly in their kids’ lives. This leaves young heroes like Percy to fend off cosmic threats alone. It’s a fresh spin. But it echoes the mythological Zeus’s habit of meddling indirectly, like when he disguises himself to woo mortals.

Poseidon, lord of the seas, emerges as Percy’s enigmatic father. He embodies the god’s dual nature from Greek tales. Ancient sources portray him as a volatile force. He commands earthquakes that split the earth and tames horses as gifts to humanity. His temper could summon tidal waves or calm the oceans for favored sailors. This reflects the unpredictable Mediterranean seas that shaped Greek life. In the series, this translates to Percy’s hydrokinetic powers. He can summon waves to surf on or heal wounds with seawater. Poseidon himself appears as a distant yet protective figure. He gifts his son a magical pearl during perilous quests. Unlike the often vengeful Poseidon of myths, who cursed Odysseus for blinding his son Polyphemus, Riordan’s version softens the edges. He makes him a supportive dad navigating divine bureaucracy. Yet the core remains. He is a god whose realm is as vast and moody as the ocean itself.

Hades, ruler of the Underworld, often gets a bad rap in popular culture as the villainous devil figure. But Greek mythology paints him more as a stern judge than a malevolent force. He oversees the dead with fairness. His realm is a shadowy mirror to the vibrant world above. It is complete with rivers like the Styx for oaths and fields for the neutral souls. In The Lightning Thief, the first book, Hades falls under suspicion for stealing Zeus’s master bolt. This is a plot twist that plays on his historical exclusion from the Olympian inner circle. Riordan redeems him. He reveals deeper motives tied to his neglected domain. This is much like myths where Hades rarely ventures topside but fiercely guards his prizes, such as Persephone. This portrayal humanizes him. It highlights the gods’ familial rifts that fuel the series’ conflicts.

Other Olympians shine through with personalities that blend myth and modernity. Athena was born fully armored from Zeus’s forehead in a tale of intellect over brute force. She mothers Annabeth Chase, whose strategic mind and architectural genius echo the goddess’s domains of wisdom and defensive warfare. Ares is the bloodthirsty war god scorned by his peers for his chaotic brutality, as opposed to Athena’s calculated battles. He appears as a leather-jacketed antagonist. He goads Percy into fights that test his heroism. Apollo is the golden boy of sun, music, and prophecy. He brings charisma to Camp Half-Blood’s oracle system. His lyre-strumming vibes are straight from myths where he slays the Python to claim Delphi. Even bit players like Dionysus, the wine god punished by Zeus to oversee the camp with perpetual grumpiness, nod to his bacchanalian revels turned sour. Demeter frets over nature’s decay. Hephaestus tinkers in forges. Aphrodite weaves romantic entanglements. Hermes dashes as a sly messenger. Hera stirs jealousy-fueled plots. These gods are immortal yet flawed with jealousy, pride, and wandering eyes. They drive the narrative’s chaos, just as their ancient counterparts did in tales that warned of divine caprice.

Transitioning from the lofty gods to their earthly offspring, the concept of demigods bridges the divine and mortal realms in both ancient Greek stories and Percy’s world. In mythology, these half-divine beings like Heracles (Hercules to Romans) or Perseus were born from godly dalliances with humans. They were tasked with labors that proved their mettle and maintained cosmic balance. Heracles’s twelve feats, from slaying the Nemean Lion to capturing Cerberus, weren’t just adventures. They symbolized the struggle against chaos. They drew from oral traditions compiled in works like Apollodorus’s Library. Demigods often met tragic ends. Their hubris or fates sealed their legacies in epic poetry.

Riordan revitalizes this archetype with Percy, a son of Poseidon whose ADHD-fueled battle reflexes and dyslexia, tuned for ancient Greek rather than English, make him a relatable underdog. Like Odysseus in the Odyssey, Percy embarks on a hero’s journey. This is inspired by Joseph Campbell’s monomyth framework. He faces trials that forge his character. Camp Half-Blood serves as his training ground. It is a safe haven mirroring the heroic academies of myth where youths honed skills for quests. Annabeth, Athena’s daughter, strategizes like her forebears. Grover the satyr scouts dangers, protecting demigods as nature spirits did in Dionysian rites. These modern heroes inherit powers tied to their parents, such as flight for Hermes kids or beauty charms for Aphrodite’s. But they must navigate vulnerability without direct godly aid. This amplifies the isolation felt by ancient figures like Theseus, who was abandoned in the labyrinth. By framing demigods as teens grappling with identity and destiny, Riordan makes the mythological hero’s path accessible. He turns epic quests into coming-of-age tales.

No exploration of Greek mythology in Percy Jackson would be complete without the snarling horde of mythological creatures and monsters that stalk its pages. These beings were born from the primordial chaos in Hesiod’s Theogony. They test heroes’ resolve and embody fears of the unknown. Riordan doesn’t just name-drop. He reimagines them prowling urban landscapes. He blends terror with wry humor. Take the Minotaur, the bull-headed beast of Cretan legend who devoured youths in Daedalus’s maze until Theseus slew it. In The Lightning Thief, it charges across a New Jersey highway as Mrs. Dodds’s monstrous form. This is a nod to its role as a guardian of the Underworld’s gates. Defeated but not destroyed, it reforms in Tartarus, the abyss of torment. This reflects myths where monsters like the Hydra regenerate unless cauterized.

Medusa was once a beautiful priestess turned snake-haired gorgon by Athena’s curse in Ovid’s later retelling. She runs a garden emporium in the series. Her stone gaze is hidden behind sunglasses. This is a clever update on Perseus’s mirrored shield victory. The Furies are winged avengers of blood crimes from Aeschylus’s Oresteia. They pursue Percy as shrieking lawyers in the mortal world. Their relentless justice is twisted into bureaucratic menace. Then there’s the Chimera, a fire-breathing hybrid of lion, goat, and serpent from Heracles’s labors. It ambushes Percy in a museum fountain. Or consider the Hydra, whose multiplying heads echo its marshy swamp origins. Cerberus is the three-headed hound guarding Hades’s realm. It gets a playful scene with a red rubber ball. This humanizes the beast from Virgil’s Aeneid.

Even allies like satyrs and Cyclopes get modern makeovers. Grover is a satyr protector. He munches tin cans and quests for the wild god Pan. This ties into Dionysus’s woodland followers known for pipe-playing and debauchery. Tyson is Percy’s Cyclops half-brother. He forges weapons with a gentle giant’s heart. This contrasts the man-eating Polyphemus from the Odyssey whom Odysseus outwitted with wine and cunning. The Nemean Lion is impervious to weapons in myth. It prowls as an invincible subway beast. By placing these mythological creatures in everyday spots, such as a Lotus Casino trapping souls in eternal gaming, Riordan shows how ancient fears persist. These include monstrous appetites and seductive distractions. The Lotus-Eaters’ forgetful blooms become a Vegas casino’s addictive slots in the series. They trap souls in digital bliss akin to Homer’s sailors.

Delving deeper into the fabric of these tales, key mythological concepts anchor the series in Greek cosmology while adapting to narrative needs. The Mist is that ethereal shroud concealing godly antics from mortals. It draws from myths where deities veiled their forms, such as Zeus as a golden rain to seduce Danaë or Athena as a mentor to Odysseus. In Percy Jackson, it explains exploding buses as “gas leaks.” This allows the divine world to hum parallel to ours without mass panic. It is a practical evolution of the ancients’ belief in hidden wonders.

The Oracle of Delphi is history’s most famous prophetic site. It inspires Camp Half-Blood’s green-misted seer. In reality, priestesses inhaled vapors to channel Apollo’s cryptic verses. They guided kings and heroes like Croesus toward ambiguous fates. Riordan’s version is embodied first by Rachel Elizabeth Dare. She dispenses quests with riddles that twist like Oedipus’s doomed oracle. This forces demigods to interpret destiny amid uncertainty. The Underworld itself is a faithful yet jazzed-up replica. It is Hades’s domain, entered via Hollywood’s Lotus Casino in the books, which is a Vegas nod in adaptations. It features the soul-sorting River Styx, blissful Elysium for heroes, punitive Tartarus for titans, and the drab Asphodel Meadows for the indifferent. This mirrors Virgil’s guided tour in the Aeneid. But Riordan adds personal stakes, like Percy’s bath in the Styx granting invulnerability at the cost of an Achilles’ heel, which is emotional and centers on his loved ones.

Overarching it all looms the Titan War, the series’ epic clash. It echoes the Titanomachy from Hesiod’s Theogony. There, young gods led by Zeus overthrew Kronos and his primordial siblings, who had devoured their own children in paranoia. Kronos’s return in The Last Olympian revives this cyclical strife. Titans like Atlas and Hyperion rally monsters against Olympus. It’s a direct lift. But Riordan infuses it with demigod agency. He lets Percy’s generation tip the scales rather than divine fratricide alone.

Artifacts and symbols from myth further ground the action. They serve as plot engines and nods to heritage. Percy’s sword is Riptide (Anaklusmos in Greek, meaning “wave breaker”). It disguises as a pen. This evokes the gods’ shape-shifting gifts to heroes like Perseus’s adamant blade for slaying Medusa. Zeus’s Master Bolt is stolen in the opener. It is the ultimate scepter of power, crafted by Cyclopes as in myth to dethrone Titans. Its theft sparks a quest that mirrors divine squabbles in the Iliad. The Golden Fleece is a healer of poisoned lands from Jason’s Argonaut saga in Apollonius Rhodius’s epic. It restores Thalia’s tree in The Sea of Monsters. Its ram-born magic is intact, but the quest is now a pirate-ship adventure. The Labyrinth is Daedalus’s inescapable puzzle housing the Minotaur. It becomes a sentient network burrowing under America in The Battle of the Labyrinth. Its shifting walls trap foes as in the original Cretan horror. But now it is laced with modern traps like automated doors.

These elements aren’t mere props. They symbolize the enduring clash between order and chaos in Greek thought. As Percy wields Riptide against the Hydra, we see echoes of Heracles’s club. This reminds us that heroism transcends eras.

At the series’ core lie timeless themes and motifs from Greek mythology. They are rekindled to resonate with today’s readers. Fate versus free will haunts many ancient narratives, from the inescapable prophecies in Sophocles’s Oedipus Rex, where a king’s doom is foretold at birth, to the gods’ strings pulling heroes like marionettes. Percy grapples with a Great Prophecy naming a Big Three child as Olympus’s savior or destroyer. This mirrors Oedipus’s tragic path. But it allows Riordan to emphasize choice. Percy’s loyalty defies predestination. He turns fate into a collaborative script.

Hubris is the Greeks’ cardinal sin of overweening pride. It felled icons like Icarus flying too high or Achilles raging in the Iliad. In the books, it manifests subtly. Annabeth’s intellectual arrogance blinds her to emotional risks. Percy’s fierce protectiveness borders on recklessness. These serve as personal Achilles’ heels that demigods must overcome. This is much like ancient heroes learning humility through suffering.

Hospitality, or xenia, was sacred in Greek society. It was a pact between hosts and strangers enforced by Zeus himself, as seen in the Odyssey where violations invite divine wrath. Riordan modernizes it amid betrayals. Demigods seek refuge in motels or islands, only to face Circe’s spa-turned-prison. This is a floral update on her transformative enchantments. These motifs weave a tapestry of moral complexity. They show how ancient Greek stories probe human nature, flaws and all.

Riordan’s genius lies in his modern adaptations. He seamlessly integrates Greek mythology into our hyper-connected age. Mount Olympus atop the Empire State Building isn’t whimsy. It is a statement on cultural migration, as Western civilization’s roots shift from Athens to New York. Gods commute via divine chariots. Their ancient egos clash in boardroom-like councils. Monsters adapt too. The Lotus-Eaters’ forgetful blooms become a Vegas casino’s addictive slots. They trap souls in digital bliss akin to Homer’s sailors. Even demigods’ struggles mirror millennial angst. ADHD becomes hyper-vigilance for ambushes. Dyslexia is a brain hardwired for heroic scrolls. These make mythological burdens feel immediate and empathetic.

This fusion democratizes myths. These were once elite oral traditions for symposia. Now they are bingeable adventures for global audiences. By setting quests in subways and malls, Riordan bridges eras. He proves Greek lore’s flexibility.

When assessing sources and accuracy, Riordan’s fidelity shines through diligent research. He draws from primaries like Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, Hesiod’s Theogony for cosmic origins, and Apollodorus’s Library for hero catalogs. He also uses later compilations by Ovid and Virgil. Core traits endure: gods’ domains, family trees, monster weaknesses. Poseidon still shakes earths. The Underworld’s geography matches Hades’s mythic blueprint. The Titanomachy retains its generational war vibe.

Yet creative liberties abound for storytelling punch. Gods’ American accents and pop-culture quips are pure invention. They are absent in austere ancient texts. The Big Three pact, barring demigod births, amplifies drama but isn’t canonical. Though it nods to myths where divine kids like Dionysus sparked wars. Kronos as a scythe-wielding tyrant is faithful. But his army’s modern recruits stray from primordial purity. Medusa’s tourist-trap shop adds levity to her tragic curse. These departures enhance accessibility without gutting essence. This is much like how Greeks varied tales regionally. Riordan consulted scholars. He ensures Percy Jackson myths educate subtly. Fans often pick up Theogony post-series.

In reflecting on why reinterpreting Greek mythology matters today, consider our fractured world. It is hungry for shared narratives amid division. Percy Jackson revives these ancient stories not as dusty relics but as living lessons in resilience, diversity, and questioning authority. By centering neurodiverse heroes and flawed gods, Riordan fosters empathy. He shows that even immortals err. For a generation scrolling through chaos, Percy’s quests remind us that heroism lies in community and courage. They keep Olympus’s thunder alive. Whether you’re a demigod at heart or a myth enthusiast, the series proves this: the old gods never truly fade. They just get a New York upgrade.

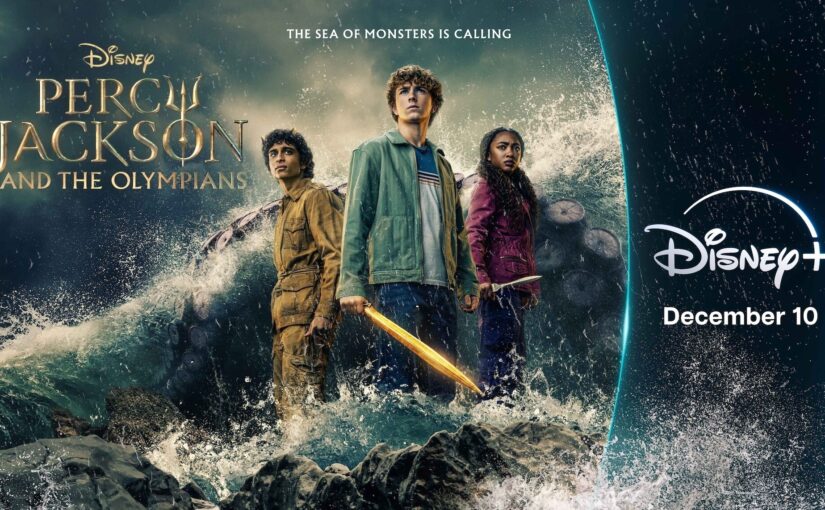

Season two of “Percy Jackson and the Olympians” is based on the second installment of Disney Hyperion’s best-selling book series titled “The Sea of Monsters” by award-winning author Rick Riordan, and premieres December 10, 2025, in the United States.